XII century building

From the first establishment of the Vicars in Vicopisano, there was a need for a place to hold prisoners who came under the criminal jurisdiction of the Vicar and his Court. Palazzo Pretorio proved to be suitable for this task and therefore housed not only the Vicar's residence but also the vicarial prisons. As early as the 16th century, prisons were divided into public and secret prisons, a distinction that was to persist in the following centuries.

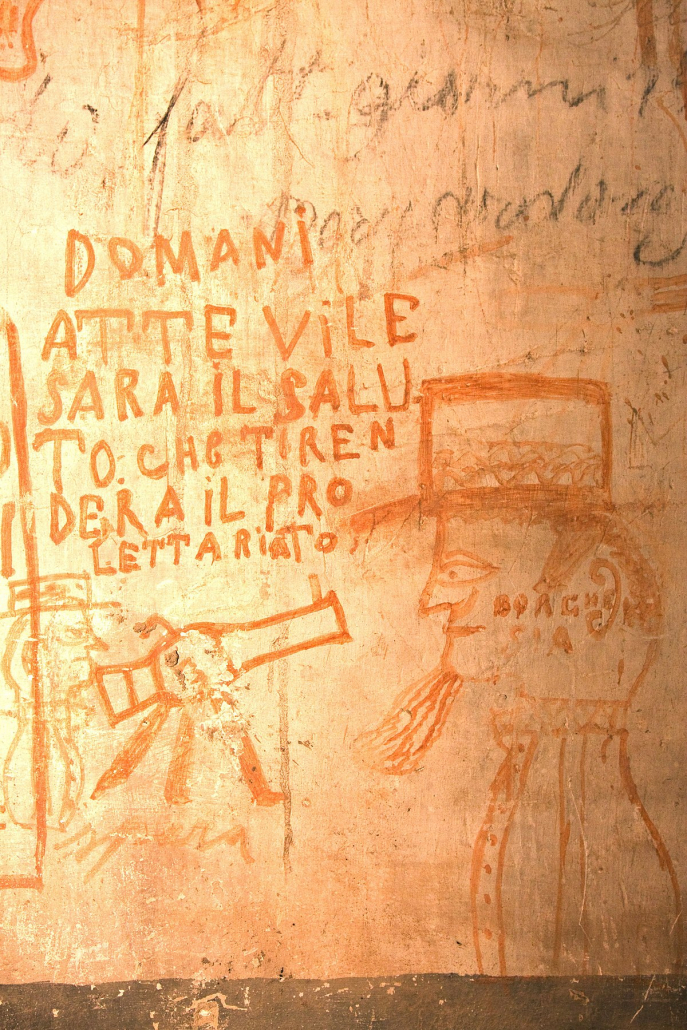

And the thousands of prisoners who, over 500 years, were kept inside the prisons could not fail to leave a trace of their passage, and in fact thousands of prisioners' writings are still preserved today, a precious testimony to suffering that has now been forgotten.

After the abolition of the Magistrate's Court and the Prison in 1923, the structure was subdivided and modified to accommodate private residences until the mid-1980s, when it was completely abandonated.

Public Prisions

These prisions, located on the ground floor of the Palazzo, are separated into two areas: the female and male public prisons.

In reality, to this day we don't know exactly whether the prisons occupied the same spaces in the 15th century as they do today. In all likelihood, the process of forming the prison complex was a fairly long one, spanning three centuries, from the 15th to the 18th century. Certainly, the prisons must never have looked very different from their present-day counterparts, as the Florentines were forced to use a fairly restricted and already "characterised" space, with very thick load-bearing walls, in which it was difficult to make doors or destroy walls without jeopardising the entire stability of the building. There are currently three cells, facing a corridor that also provides access to the latrines. Once inside the Prisons, one notices the considerable height of the ceilings, not very appropriate for a medieval prison.

In fact, the prison was used from the 15th century onwards, but it should not be forgotten that we are inside a building constructed in the 12th century for an entirely different purpose, so that the subdivision of the internal spaces was that of a civil domus and had no public function, as the Palazzo would assume from the 15th century onwards.

It is not difficult to imagine that the living conditions in the prisons between the 15th and 17th centuries were not at all easy, and some 17th-century documents preserved in the local Historical Archives give a description of the cells in which the miserable state the prisoners were forced to endure is very clear from the plan attached to them: there was no light or air exchange, there were no toilets, but a common hole in the first cell was used, and there was no possibility of heating, so they were forced to light a fire in the middle of the room, but since there was no chimney the room quickly filled with smoke (even now you can see a strong presence of soot under the first eighteenth-century whitewash).

The current appearance of the prisons is due to the modernisation work carried out from the 18th century onwards, which gave them a more humane appearance.

Secret Prisons

These prisons are located on the second and third floors of the palace, and their access is immediately above the Hall of Torment.

The secret prisons were in turn divided into two areas: the actual dungeons, corresponding to the four cells on the second floor, and the Rooftop Dungeons, two of which were larger and two smaller and more cramped.

Even for the dungeons we don't know when they began to be used (the first document mentioning them is from 1575) nor whether they were always used for detention purposes. The access doors are still made of wood, with peepholes and latches still preserved.

The names of some of the cells in the secret prisons have survived: the Spogliatoio (changing room), the hallway onto which the dungeons face, the Segreta del Paradiso (Paradise Secret) and then the Segrete della Barca, dei Mattaccini and dello Stellino. Once past the main entrance door, one notices the entrances to the cells mentioned above, which are very low and narrow, with well-preserved doors. It is in these prisons that the most consistent traces of the Palazzo's medieval phase remain: in fact, the beautiful large ogival windows are still visible, which underwent a reduction in size and the addition of grilles when it was transformed into a prison.

What is striking in these cells is the presence of many writings, mostly from the 20th century, which are a living testimony to the presence of the prisoners and their dreams of redemption and revenge: these are traces left by the anarchists and communists arrested in the period from the early years of the century to the twenty years of Fascism, who were often detained under preventive measures to prevent them from carrying out subversive activities during demonstrations or important visits. For this reason they enjoyed a relative freedom of movement, which allowed them to decorate all the walls of their cells with their proclamations of struggle, something that is present on the other floors, but not in such a massive and evident way.